The answer, as of today, is that we all do — and yet, paradoxically, most of us have no say in how it’s governed (outside of oligarchically designed “democratic” elections). What if, instead of treating AI as private property or a geopolitical weapon, we treated it as a collective good — a “commons”?

That idea might sound utopian, but it isn’t new. Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom spent her career dismantling the myth that shared resources inevitably collapse into chaos. Her research, synthesized in Governing the Commons, proved that communities are capable of managing collective resources responsibly when they design inclusive, layered, and locally grounded rules. She studied irrigation systems, fisheries, forests, and pastures — but in our time, the shared resource is data and the algorithmic architectures it feeds will make or break the next few generations on how we work – and if we work at all. Leading innovators have been talking UBI (universal basic income) and other alternatives to governing AI innovation, and this is not new. Publicly subsidized technological advances and innovations are not new to the US, or to the AI leading innovator and socialist nation – China. The US funded AT&T and later broke up the government sanctioned monopoly they caused; this could be the reality of governance and regulation in 50 years if we don’t do something to curtail the monopolization of key industry leaders of AI.

AI as the New Common-Pool Resource

Ostrom defined a common-pool resource (CPR) as a system where one person’s use reduces the availability for others, and where exclusion is costly. The water in a shared aquifer, for instance, is finite: if one group over extracts it, everyone suffers.

AI fits this definition more closely than most people realize. It is not merely an abstract algorithm — it feeds on data, energy, and human input. Each prompt typed into a chatbot, each piece of personal data mined for training, each kilowatt-hour consumed by an overworked data center contributes to a finite global system. The training of large language models, for instance, already requires enormous energy and water resources. In a warming world, these inputs are anything but infinite. Water, rare earth materials, chips manufactured by key industry leaders, and even the data it utilizes to process is finite (even if it seems infinite).

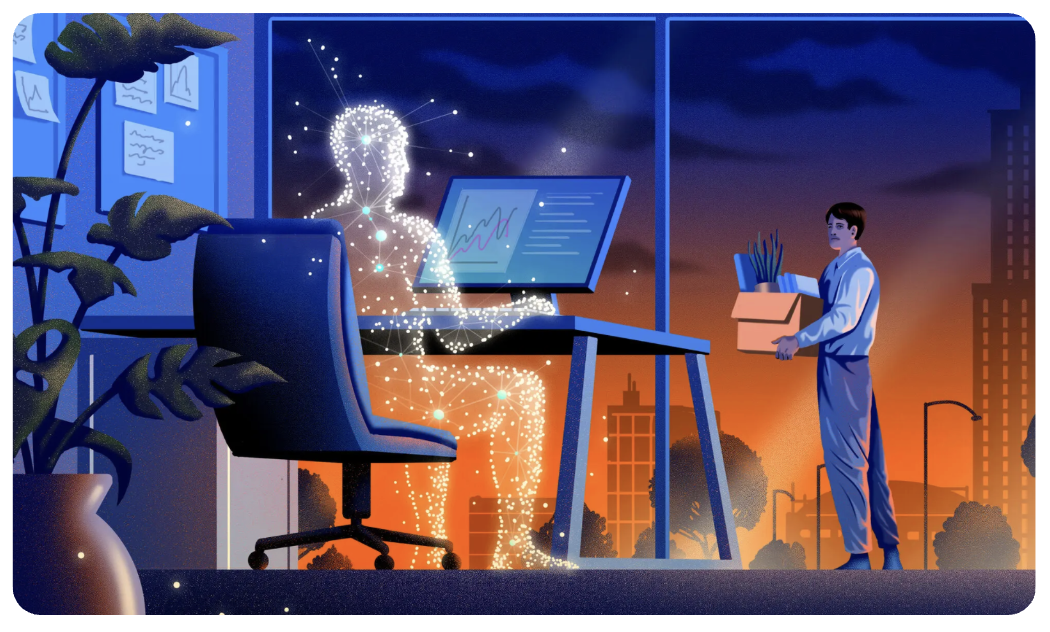

Worse yet, the governance of AI is profoundly asymmetrical. A few dominant corporations and nation-states are effectively privatizing what should be an evolving global good. The benefits — productivity, profit, capital accumulation — accrue to a narrow circle. Meanwhile, the externalities — job displacement, surveillance, information bias, and environmental damage — are collective.

The Myth of the “Tragedy”

Governments often act as though unregulated technological innovation will naturally solve social problems. But Ostrom argued that the so-called “tragedy of the commons” is not inevitable. It becomes a tragedy only when communities are denied the ability to design and enforce their own governance rules.

In the case of AI, communities lack both voice and visibility. Citizens whose personal data trains algorithms are excluded from decision-making. Workers displaced by automation have no role in determining how or when machines replace them. Even national regulators play catch-up, scrambling to legislate technologies already in global circulation.

This is not a tragedy of overuse, but of exclusion. The people contributing value — users, data providers, and affected workers — are rarely recognized as legitimate stakeholders. Without transparent participation, decisions default to those with concentrated power: the firms that own the models and the governments seeking to control them.

Applying Ostrom’s Principles to AI Governance

Ostrom developed eight design principles for successful commons governance, each offering insight into AI’s current failures — and possible remedies.

- Clearly Defined Boundaries:

- AI’s boundaries are fluid and opaque. The “resource” includes data, code, and infrastructure scattered across jurisdictions. We need transparency on who trains AI, where, and on what data. Clearly defined data rights — especially ownership and consent — are the foundation of a sustainable AI ecosystem.

- Congruence Between Rules and Local Conditions:

AI regulation cannot be one-size-fits-all. Ethical norms in Europe differ from those in Africa or South Asia. Local contexts should shape data governance, reflecting cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic diversity. Regionalized AI institutions could ensure that rules match local realities rather than imported standards.

- Collective-Choice Arrangements:

Diverse stakeholders — particularly workers and communities most affected by automation — must have a voice in defining the rules of AI adoption. Polycentric governance, or shared decision-making across different scales, empowers more inclusive oversight.

- Monitoring:

Right now, the only consistent “monitors” of AI systems are the companies that build them. We need independent algorithmic auditors and public interest watchdogs. Transparency in model design and deployment should be a regulatory requirement, not a PR strategy.

- Graduated Sanctions:

Ostrom found that effective communities impose penalties for misuse. Current AI regulations rely on voluntary compliance or post-hoc litigation. Proactive sanctions could include tiered fines, algorithmic suspensions, or trade restrictions for firms violating ethical norms.

- Conflict-Resolution Mechanisms:

Disputes over AI misuse — from deepfake harms to data theft — are resolved through slow, expensive legal channels. We need accessible, low-cost mechanisms such as community data councils or rapid digital arbitration models.

- Recognition of the Right to Self-Organize:

Communities affected by AI should be empowered to design their own governance systems. This could mean cooperative AI ventures, citizen-led data trusts, or regional AI commissions that reflect local priorities.

- Nested Enterprises:

Finally, successful governance operates across layers — local, national, and global. Multilateral treaties, national laws, and local ethics boards must coordinate, forming a polycentric ecosystem rather than a monopolistic one.

The beauty of Ostrom’s framework is that it recognizes both autonomy and interdependence. No single institution, not even the United Nations, can govern AI alone. But together, overlapping institutions can create a resilient mosaic of accountability.

From Polycentric Governance to Polycentric Trust

Ostrom’s later work emphasized polycentricity: multiple centers of governance that balance each other’s incentives. Applied to AI, this means distributing control across sectors — governments, private industry, academia, and civil society — to prevent any one node from dominating.

This approach is more flexible than either deregulation or central control. It acknowledges the rapid pace of innovation while insisting on democratic oversight. It also invites trust-building. In economics, trust reduces transaction costs; in governance, it enables cooperation. Without it, global AI policy collapses into mutual suspicion — a digital arm race where each actor hoards its algorithms behind national or corporate walls.

Reframing the Economic Question

Critics will argue that regulating AI like a commons could hinder innovation. Yet Ostrom taught that well-designed institutions enable innovation by ensuring fair access and shared responsibility. When properly managed, commons outperform both open-access chaos and rigid central control.

Economically, AI’s greatest risk is not overuse but inequitable distribution. High-skilled workers benefit from AI complementing their skills, while low-wage workers are displaced by automation. Developed nations hoard the infrastructure and capital, while developing ones are left as data suppliers and resource extractors. If we continue governing AI through market concentration and techno-nationalism, these inequalities will deepen.

Treating AI as a commons, by contrast, would mean opening channels for equitable participation: data governance frameworks that return value to contributors, open-source collaboration that democratizes innovation, and cooperative AI models that align machine learning with human welfare.

The Commons We Deserve

AI is neither villain nor savior. Like all technologies, it reflects the systems that govern it. Ostrom’s legacy reminds us that collective challenges can produce collective ingenuity — if we trust communities to participate in their own future.

The question is not whether AI will shape our world, but whether our governance systems can evolve fast enough to guide it. The answer won’t come from a single law, algorithm, or company memo. It will come from the slow, complicated, democratic work of building a global commons — one that recognizes data, innovation, and human dignity as shared resources, not commodities to be exploited. We have the tools. We just need the governance to match.